The challenge with blogging, when you are travelling and finding new stimulation every day, is trying to keep up with the writing. For instance the Thursday before last I travelled from Nuremberg to Chemnitz, in what was part of the former German Democratic Republic, now but a memory, twenty five years after its demise.

I had the good fortune to be invited to meet there, with the remarkable Dr Marcus Horsch, from Leipzig University. Dr Horsch, is an authority on German Medieval and Renaissance sculpture, and through his current research, is documenting the outstanding sites, in the old GDR and Czech Republic. A unique task, that requires a passionate man. Dr Horsch is that man, and I was the beneficiary of his specialist knowledge.

One of the original catalysts in encouraging me to apply for this Churchill Fellowship, was reading the English historian Michael Baxandall’s fascinating introduction, to the otherwise marginally known story, of the Late Renaissance Limewood Carvers of Germany. I found his account of this period, and the deep humanism it’s oeuvre conveys, compelling. I felt drawn to experience this work intimately for myself, certain that the pictures in the book, could hardly do justice to the sculptors’ achievements.

Much of Baxandall’s research, carried out prior to the collapse of the GDR, was in southern Germany, and drew heavily on the excellent collection of the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in Munich. It illuminated some of the already more familiar names like Tilman Reimenschneider, Adman Kraft and Viet Stoss. Sources in Germany assured me that the Baxandall coverage was incomplete.

Dr Horsch, who has a profound respect for the sculptors of this period, wanted me to travel in Saxony ( formerly in the GDR) with him, to see some of the Gothic treasures, which the GDR times had neglected.

Neglect was in fact a state policy, and the marvels that are the legacy of the Medieval makers, and builders, suffered as a consequence. It is then, uplifting to see the fine restoration that has taken place over the past twenty five years and continues, to this day.

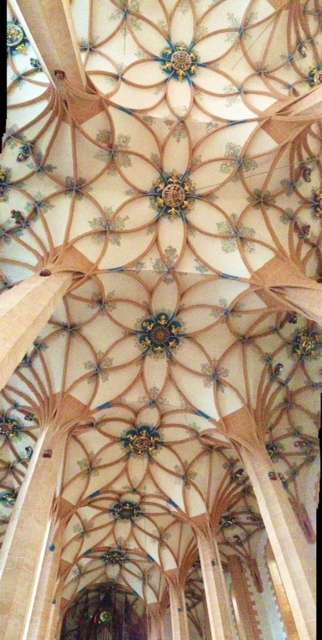

One of many treasures, the good doctor was determined I should see, was in the beautiful St Anne’s Lutheran Church in Annaberg. In the middle ages St Anne, the mother of Mary, was revered as the patron saint of miners. As a prosperous silver mining town, in its renaissance heyday, Duke Georg of Saxony decreed that, Annaberg should have an orderly pattern of development, and that its existing wooden church, should be replaced by a more prestigious stone building. This was begun in 1499, and finally completed in 1525. What was achieved, remains to this day, with a pervading aura of dignity, that is both majestic and graceful.

No other Gothic church is quiet so “vegetal”, so natural in design. The ribs which sprout from the knave bend like supple willows around the pillar shafts, and the ceiling rises like a petalled canopy above each bay.

The ‘treasure ‘ I was there to see, inside this majestic building, the so-called “Beautiful Door’, bears the initials H L, believed to be those of the master, Hans Witten.

Originally made for the Franciscan monastery in Annaberg, which was Duke Georg’s other devoted project, the door was moved to its current placement in St Anne’s in 1577, after the monastery had been secularised in 1539, and its buildings had fallen into disrepair (a familiar story). It is interesting to note how frequently, in the course of history, the intended home of works of art, has changed as a result of unfolding events. In this case, how fortunate for St Anne’s ?

Hans Winton’s deep humanism, asserts itself forcefully, into the buildings majestic interiors. Sculptors, such as Winton, were intellectually great conceptualists, as well as gifted carvers and designers. Here the doorway is conceived as a ‘sculpted image’, with St Francis interceding before the throne of mercy, drawn from a vision he described: The mother of God appeared to him in a dream and so he asked Christ that all that came to his church in penance, receive total absolution.

This lay visitor, from another age, was hypnotised by the clarity of Hans Witten’s concept. Despite that gulf in time and space, I was, if only momentarily, transported to a present, far beyond the erratic pulse, which the twenty-four hour news cycle makes so inherent today.

In this blog post Australian sculptor Stephen Hart explores The Past is Present in Annaberg.

St Anne's Church

St Anne's Church  The " Beautiful Door ".

The " Beautiful Door ".  From the "Beautiful Door "

From the "Beautiful Door "  St Anne in silent prayer

St Anne in silent prayer  H W inscription, the "Beautiful Door ", St Anne's church, Annanberg.

H W inscription, the "Beautiful Door ", St Anne's church, Annanberg.