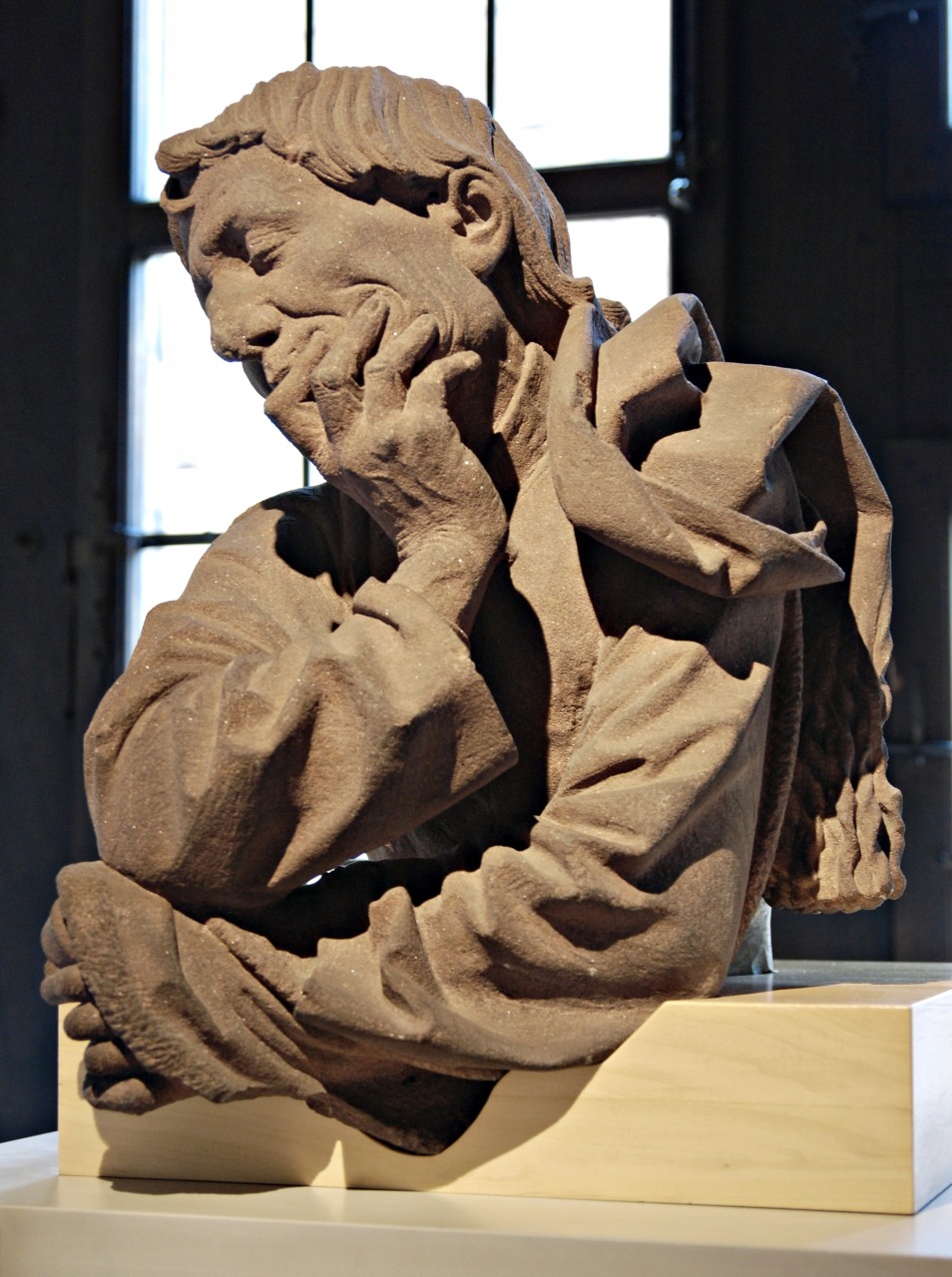

I’ve travelled from Frankfurt to Strasbourg today, with the express purpose of seeing a small stone bust of a man, who appears deep in thought. This carving has long spoken to me, with its thoughtful, melancholic presence. The integrity, contained within its form, has somehow prevailed through the millennia. I am here to understand something of the life and story it contains.

Carved in 1467 by the Flemish sculptor Nicholaus Gerhaert, this miracle in stone has exerted an influence far beyond its scale. It is something Gerhaert’s oeuvre bequeathed the generation of late renaissance German sculptors who I am still to fully encompass in my pilgrimage.

Today, in the Musee de L’Oeuvre Notre Dame, four hundred and sixty seven years later, Gerhaert’s masterpiece, still pulsates with the life its makers hand imbued it with.

I feel compelled to draw when I am in the presence of masterpieces such as this. Doing so, with my own clumsy gestures, I seek to imprint, in my own mind, something of the magic contained in the work, and in so doing enter the mind of its maker.

What happens when you stand in front of such a work, with that impulse? First of all the complexity of the sculpture, as a thing in space begins to exert itself. The various movements within it’s structure , become apparent. It appears so still at first, yet as soon as one begins to render lines to convey that presence, this apparently inert piece of stone, comes to life. In drawing it one is asking where does this life come from ?

The seeming melancholy weight of the head is drawn in thought forward of the body, arrested by a supporting right hand. Bearing that tension, the flesh folds at the wrist, and the blood vessels conducting the gesture exert themselves forcefully. The moment has gravitas, further emphasised by the way the flesh of the mouth and cheeks fold under the lightly spread fingers. The index finger is creating an opening at the mouth where slow breathing seems palpable.

The eye balls droop forward with the tilt of the head, they are held in place by the eye lids, which almost enclose them, holding their fall. But not quite. The pupils, barely visible behind convex slits, speak to a mind alive and in deep contemplation.

The elbow of that arm, rests on a left hand that is clutching something in its firm grasp.

The German Historian, Dr Markus Hoersch, tells me the hand is believed to be holding a compass. He is convinced the bust is in fact a self portrait of Gerheart indicating that he is the designer of the lost Strasbourg Cathedral portal.

If this is so, that magnificent, tendril monument, to the beliefs of another time, still resonating throughout Strasbourg Cathedral, is well amplified in the drama of the enfolding drapery Gerhaert has depicted himself wearing. His pulsing flesh,like the building he contributed so much to, echoes in his garments.

Gerhaert’s bust makes apparent the dignity of one man’s inner life and, in so doing, has made apparent for the ages, that this universal prospect, is available to all men who seek it.

Its quiet forbearance remains remarkably powerful and sustaining. Perhaps even more so today, where highly activated/ animated lives leave little time for reprieve.

In these times, with its’ unique challenges, this work remains, powerful, and sustaining. I will return to it today, and if satisfied that I have absorbed enough for now, will take a train to nearby Colmar. There Grunewald’s remarkable altarpiece, has also endured the ages but perhaps more on that later